The Last Fish

2015

PROJECT DETAILS

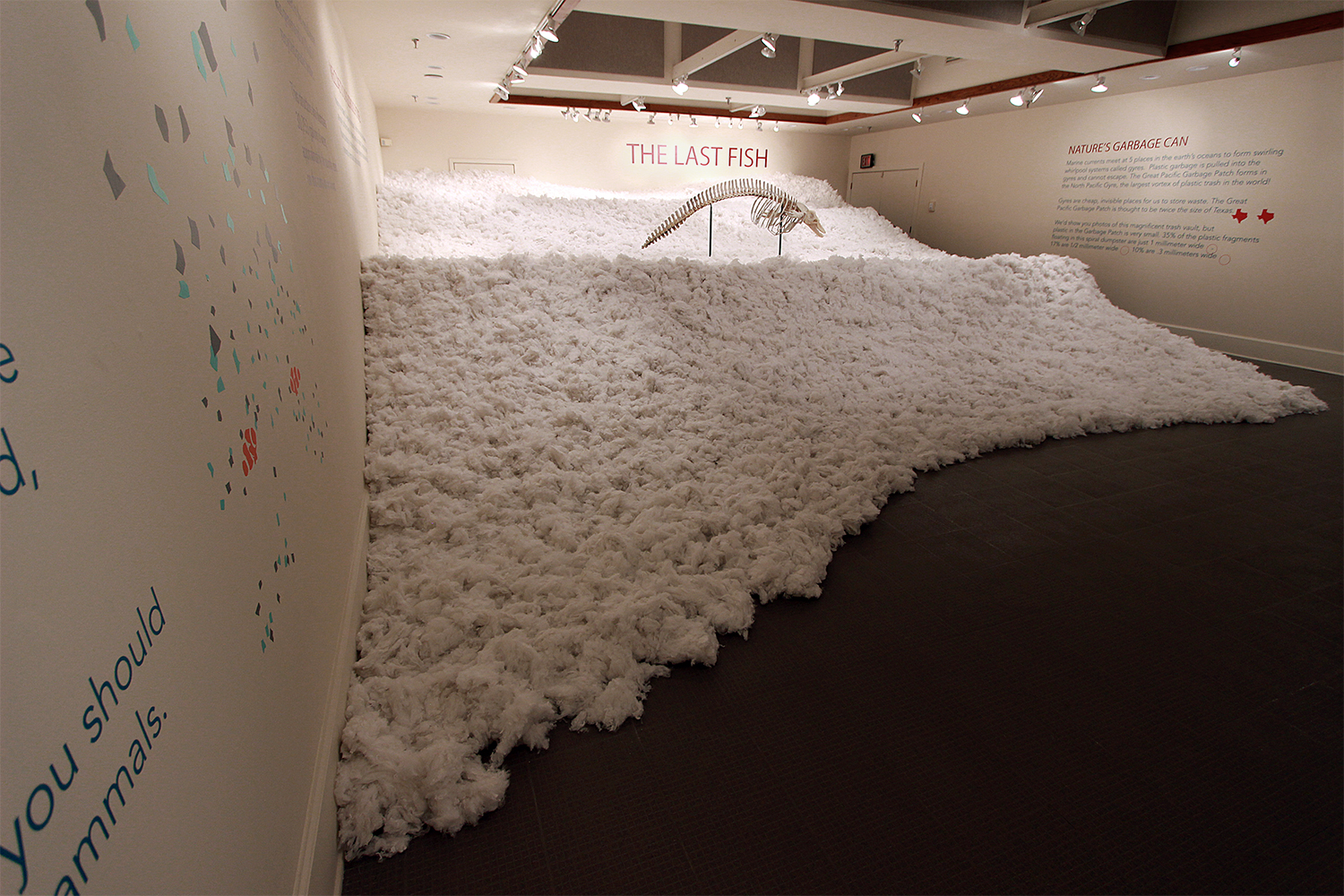

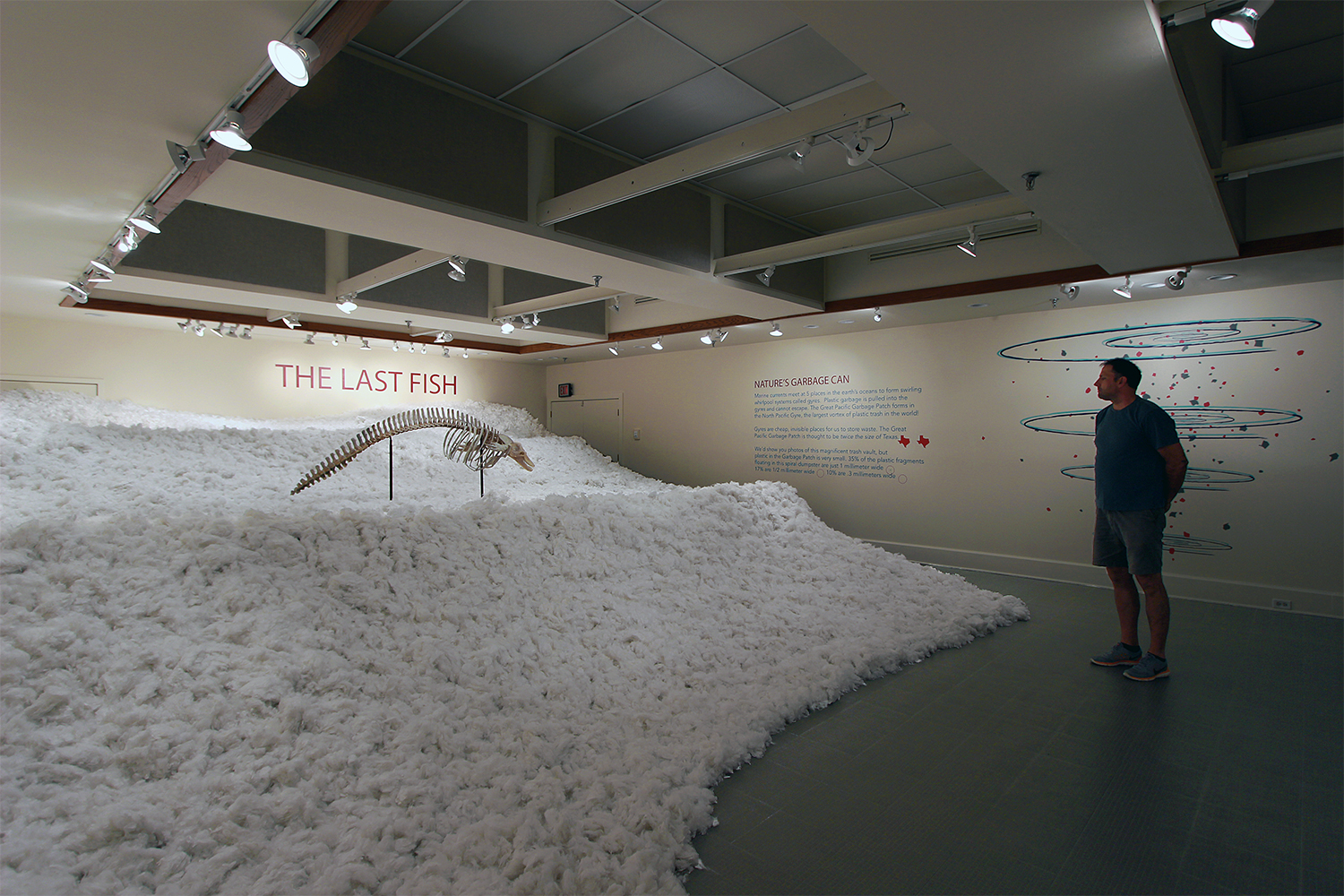

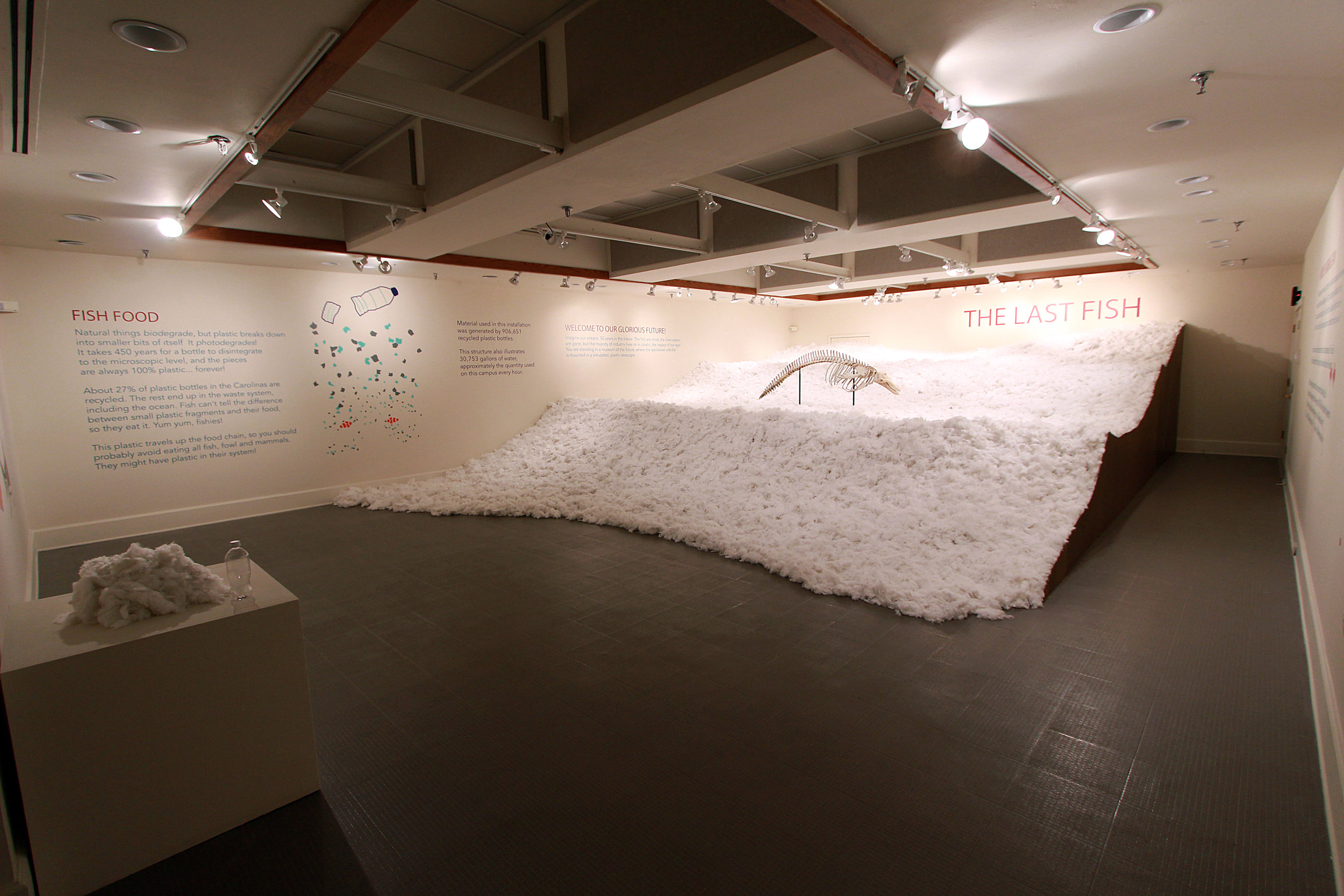

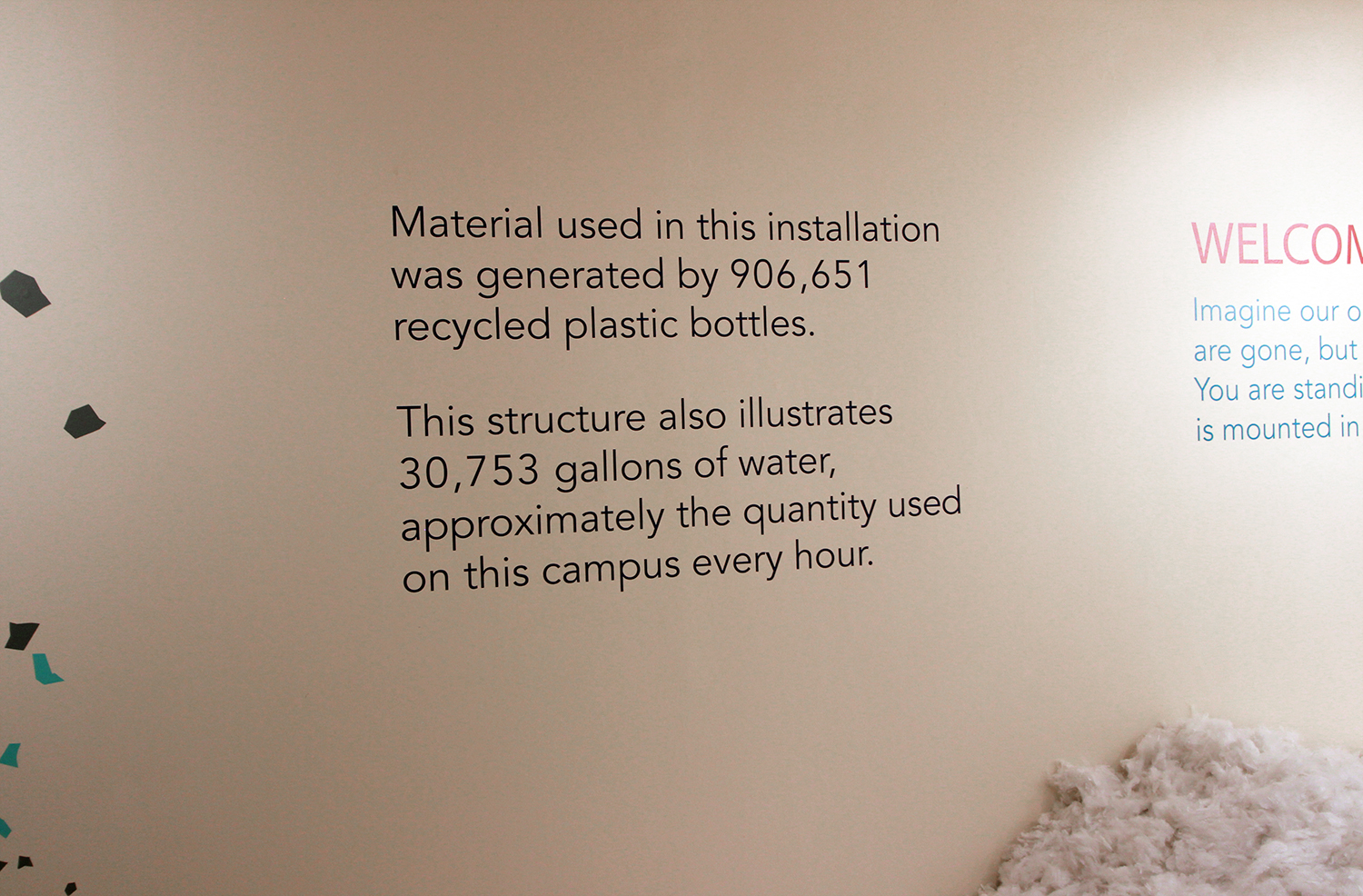

In this on-site constructed installation, my collaboration partner and I installed a portion of beach, with incoming swells and waves of water. The shoreline rose from the gallery floor to high on a back gallery wall in an awe-inspiring, large-scale representation of the landscape. Upon inspection, viewers saw that this beach was entirely constructed from regranulated post-industrial plastic, normally sold to make recycled plastic products. The impression was beauty that quickly turns to dismay.

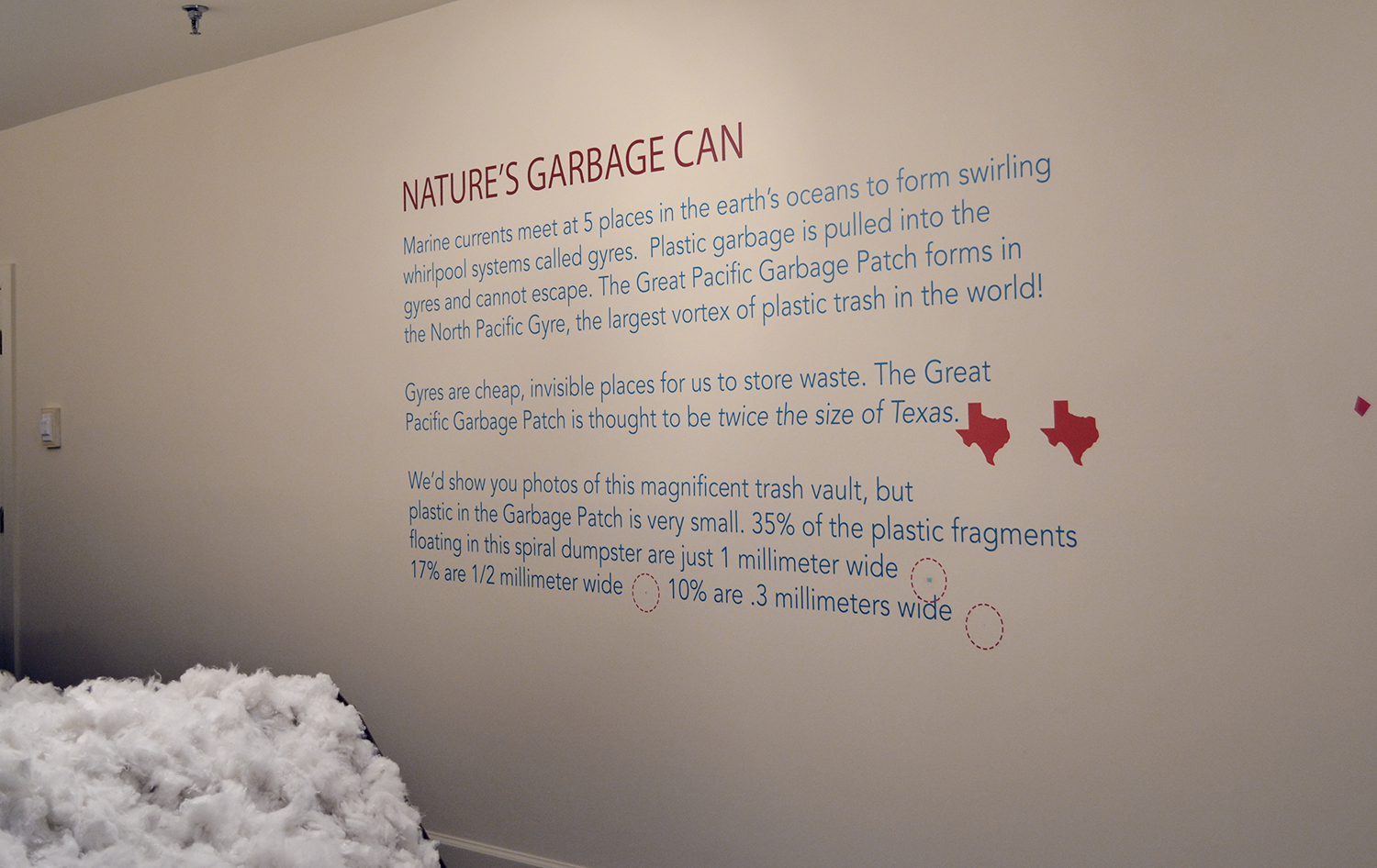

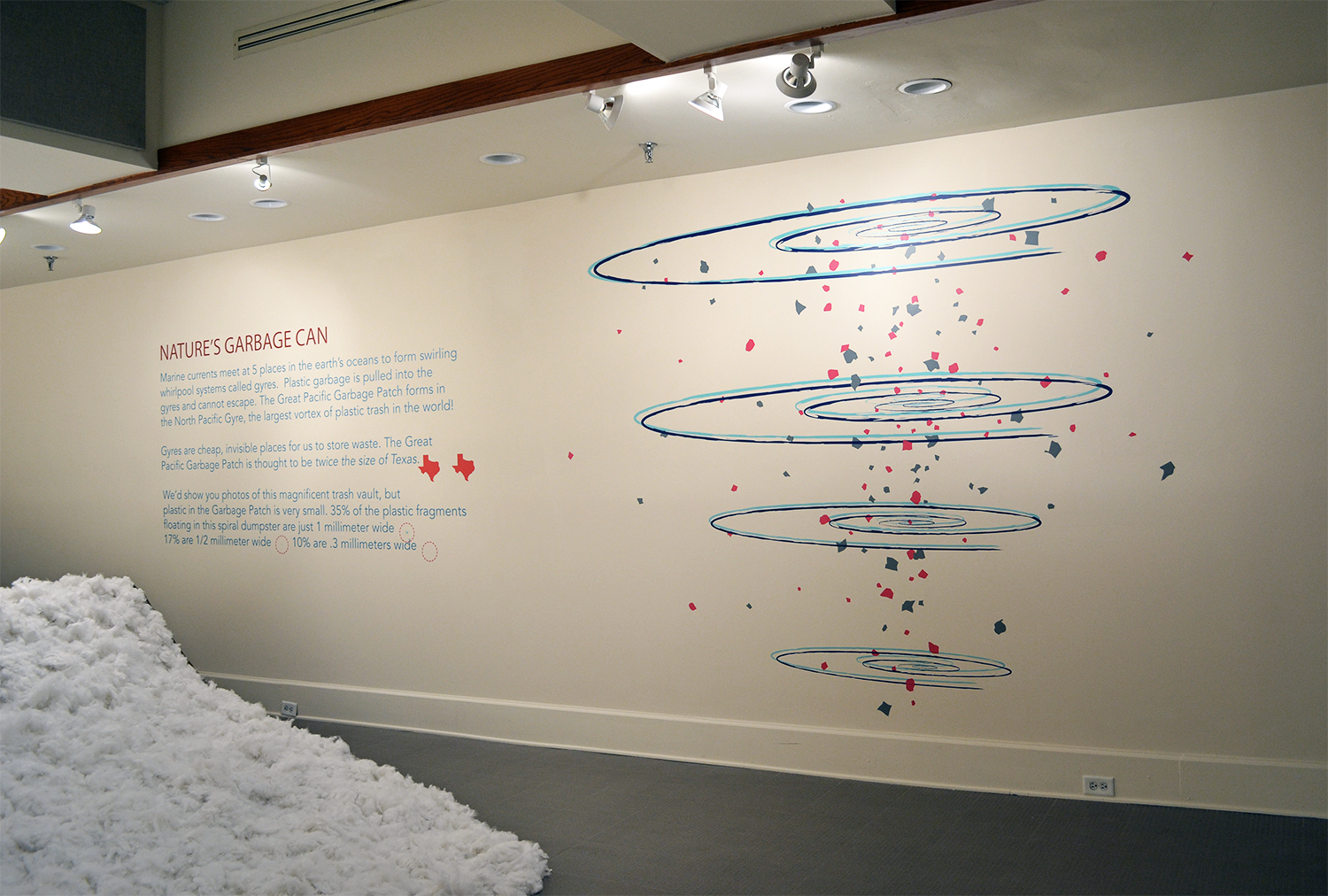

The plastic water on our beach offered a dystopic image of the future, as if there was no more clear water in the ocean, but only seas of broken-down plastic, such as what you find in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch or, more accurately, the North Pacific Gyre.

EXHIBITION

Rutledge Gallery, Winthrop University Galleries, Rock Hill, South Carolina, 2015

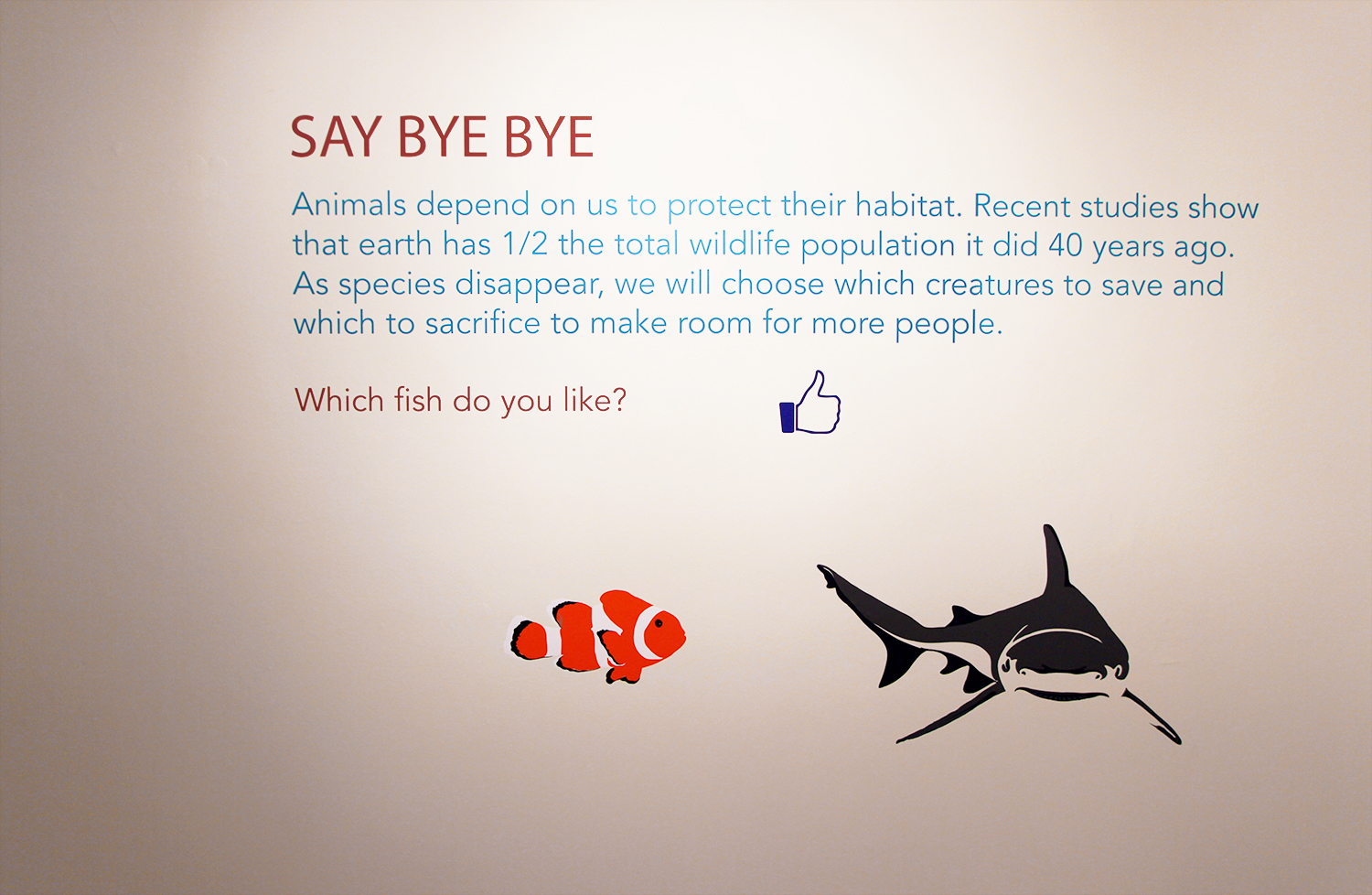

Our exhibit was presented as a public museum of the future, presenting this plastic atrocity with contentment. We fed the “present” circumstances to viewers as no big deal. This “oh well” attitude expands the mind-set of our present condition and treatment of our oceans to foreshadow what willhappen if our consuming habits remain the same. The mounted dolphin skeleton represented “the last fish” to exist on the planet. This is our future vision of a public that accepts these catastrophic changes with apathy.

The graphics within and along the edges of the exhibit explored connections between the volume of plastic in the gallery and consumption patterns:

Plastic bottles are ubiquitous in America now. We drink all our beverages from them, including our own tap water, bottled and resold to us by companies like Dannon, Coke and Nestle. Meanwhile, the water quality in our worlds’ oceans is at a critical tipping point. Plastic pollution is a primary culprit in degrading the ocean environment and threatening its inhabitants. We comfort ourselves by dutifully recycling our plastic bottles, but recycling efforts do not keep up with the demand for new plastic products. Worse, plastic does not biodegrade, but only photodegrades, which means it breaks down into smaller and smaller versions of itself. Small fish, coral and marine mammals mistake the tiny particles for plankton and regularly consume plastic as food. The consumed plastic makes its way up the food chain when larger fish, land animals and humans consume the smaller animals that have eaten large amounts of this “regranulated” plastic.

We bought the material, then donated it to a reseller who uses it in lesser products where the material can be less pure.